tv The Communicators CSPAN July 9, 2012 8:00am-8:30am EDT

8:00 am

8:01 am

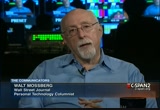

>> this week on "the communicators" i walt mossberg, who writes a personal technology column in "the wall street journal." >> host: well, regular tech watchers and viewers of this program will recognize the name walt mossberg of "the wall street journal," maybe not the face, but he is joining us this week on "the communicators." he writes the personal technology column in the "wall street journal", and he's also co-executive editor of all things d.com. mr. mossberg, when did you start writing your personal technology column? >> guest: well, peter, it was 1991, and you can call me walt. >> host: well, i appreciate that. do you remember what your first column was about in 1991? >> guest: the first line of my first column was personal computers are just too hard to use, and it's not your fault. and the idea behind the column

8:02 am

was there are a lot of computer columns at the time or technology columns, and the contribution i made was to convince the editors of the journal that we should write a column that unlike nearly all the others was not written by geeks for geeks, but was actually written to champion non-techie, smart people that were smart about whatever their business was. if they were an insurance agent, if they were a teacher, whatever it was, but they didn't know or want to know how the computer or the digital camera worked. they just wanted to be able to use it. and in those days, and i think it's hard sometimes for viewers now to remember, it was really -- you had to, basically, put in many, many, many hours and days and weeks to learn the intricacies of a personal computer. so my idea was to write this in

8:03 am

english, champion those people, not the techies and enthusiasts. and instead of being river remember cial -- reverential toward the industry, which a lot of writers were in those days, i was given full leeway to be critical of the industry for not making these things easier for average, non-techie people to use. that was the idea. >> host: so when's the last time you wrote about pcs? >> guest: oh, within the last few months. i mean, i write about -- i still review pcs. laptops, netbooks, i have a writing partner who works for me, katherine, very bright woman, who reviewed the new macbook pro last week. pcs, there are hundreds of millions of them.

8:04 am

and they're sold in large numbers every year. i think they will be eventually -- and when i say eventually, i mean probably not that long in the future -- be outsold by tablets like your ipad here on the desk, but people are snapping up pcs every second that we're sitting here in this interview and, actually, it's even more prevalent in some parts of the world outside the u.s. so i'm not done writing about pcs. and, furthermore, there's a very valid, i think, theory that says that the ipad you have here and other tablets are pcs, just in a different form,? they actually are radically different user interface. but i don't regard that as just

8:05 am

a consumption device to watch movies on, although it's great for that. i think it's a product device as well, and big companies which i don't particularly pay attention to are buying these things in the tens of thousands. >> host: walt mossberg, when it comes to technology, is there a big three, and i'm thinking of, you know, facebook, amazon, google -- >> guest: there's a big five. in fact, eric schmidt, you know, the executive chairman of google, appeared at a conference i run, this all things.com web site that i run with my partner cara swisher also has what i i think is the premier tech conference in the country, all things digital. we just had our tenth year of our conference, and eric schmidt spoke there last year, and he talked about the gang of four companies that are dominant now.

8:06 am

he was tweaking microsoft by not including them, so i'm going to say there are five. and the five are apple, amazon, google, facebook and microsoft. now, what makes those the principal competitors is that they all own platforms on which other companies are building products and services. so they control these big ecosystems in which hardware exists and services and software and apps, and they're all also competing with each other at least in certain ways. now, you might say, well, apple's a hardware company, and amazon mostly sells products and digital content, and google is mostly search and advertising. and that's true, but they all are kind of in each other's

8:07 am

business, and they sue each other regularly, so that's the big battle right now between those five, among those five. >> host: well, when those five companies started, they had one thing in summon which is they didn't care much about washington, d.c., and they didn't have any kind of washington presence. >> guest: right. >> host: now they all have a pretty prominent washington presence and growing. >> guest: yeah, they not only didn't care much about washington, they were pretty much determined to ignore government, and, you know, i think it was sort of naive to some extent. but they were, they were living in this world where they thought, hey, we're changing the world, we're innovating, we don't have any trouble raising money, we don't have any trouble attracting talent, and we can see right before our eyes that the whole world is actually changing because of the products we make.

8:08 am

so unlike those old industries -- oil, railroads, you know, whatever -- we don't need to deal with the government. i mean, obviously, they had legal departments that were involved in making sure they complied with regulations and paid taxes and all that, but other than that they weren't. and the big wake-up call really was the microsoft antitrust suit which in the case of microsoft obviously forced them to pay a lot of attention. and then, you know, in the ensuing period to really bulk up their lobbying. even then it was more than a few few -- many years before apple had people here in d.c. and as you point out, they all have significant offices here. in some cases not only for the purpose of doing traditional lobbying and so forth, but they actually have a little tech war

8:09 am

going on in the region here around d.c. >> host: so when it comes to the lobbying and the regulatory agencies here in washington and the tech companies, first of all, did the microsoft antitrust suit, was that, was it just because microsoft got too big? [laughter] >> guest: no, it wasn't just because microsoft got too big. i'm not a lawyer, but my understanding is that it's not illegal to be a monopoly, it's just illegal to use your monopoly power in certain ways. and microsoft was viewed by the justice department as kind of bullying or con constraining the companies that made p cs into certain things. and that's, of course, ancient history. there's an antitrust case involving apple and some book publishers right now. there's a google antitrust case under consideration, no case has

8:10 am

been filed. so these are -- it's not the sheer size of these companies, i think, that sometimes attracts the attention of the government as the way that they interact with the economy, the way they interact with privacy, the way they interact with commerce, and, you know, they're big, but -- and in the case of apple, they're very big in a dollar sense, but they're also very big in the sense of the impact they have on everyone's lives. and, obviously, that's going to attract the attention of regulators and enforcement agencies in this city. i will say that i've lived in washington now for nearly 40 years, and i spent 20 years as a washington correspondent and an editor here in our washington bureau before turning to technology, and my observation is that the government in

8:11 am

general is, was and still is way behind in its actual integration and use of technology on a day-to-day basis. i'll give you an example. the government is the last or one of the last major holdouts of using the blackberry. and the blackberry is a historic and important and storied device, and you never want to rule out that a company be paragraphly in tech will make a comeback. but today if you have the choice of a device to carry around, the blackberry is a severely limited device compared to an iphone or an android phone. and yet this is one of the few cities where you can walk around and see large numbers of blackberries today. you don't see it in new york, you don't see it in chicago, you don't see it in l.a., you don't see it in london, you don't see it in, you know, latin america.

8:12 am

i mean, basically the world has moved on, and washington has not. and that's kind of a symbol. when i used to cover national security in the state department, and this was 25 years ago granted, the reporters on the secretary of state's airplane -- including me -- had what was for the time much more advanced laptops than the secretary of state's officials or the cia people or the dod people on the plane. i mean, we had the best technology, and our government did not. for day-to-day use. and, obviously, things have improved a lot since 25 years ago, but at every stage as technology moves the government is the most sort of laggard. and so i think that actually effects the understanding of

8:13 am

these companies. i'm not saying that the government shouldn't be regulating them, and there was a view at one time in silicon valley that they were sort of immune to regulation. i don't believe that. but, um, but i do think that sometimes the government, congress' understanding or the white house's understanding is not where it should be. >> host: why is that? >> guest: don't know. i think there's a cocoon here to some extent. >> host: is the cocoon out in silicon valley? >> guest: i was ability to say there's a cocoon in silicon valley too about thinking about the way average people operate or the governments of the world operate. they're getting educated fast in silicon valley about that. today do everything fast. and here in washington we do everything slow. so, you know, there's a cocoon in new york about, i pose in part -- i suppose in parts of new york about the financial industry, and they don't quite

8:14 am

connect with how everyone else sees them or interacts with them. every town that is an industry town has that. and silicon valley certainly does. but the washington cocoon, one of the impacts of it, i think, has been to not allow at least the senior people. i think the junior people here are different, staffers and people are much more attuned to normal use of technology. but really very few people at senior levels in the branches of government live a digital lifestyle compared to leaders of even corporations that are not in tech have learned to live a digital lifestyle. i was recently at a meeting with a company, the whole hierarchy of a company that is not a tech company. it's got dealings with tech companies, but there's not a tech company. they've all switched to just

8:15 am

using ipads. they all were sitting there with ipads in front of them, and the ceo, the coo, the cfo, you know, the chief marketing officer, all these people, you know, thai adopted this quick -- they've adopted this quickly. in hollywood they've adopted it, you know? you see iphones and ipads and sometimes android devices in the hands of even the top people. they read their scripts on i pardon, and they've -- ipads, and they've put away their laptops. not so much here in washington. so there is a gap. >> host: well, i did bring down my personal devices, and you can see here's a blackberry and an android and an ipad. so how much of a dinosaur am i? >> guest: well, the android and the ipad are very modern. i don't know which phone this is -- >> host: couple years old. >> guest: so it's a couple years old, but, you know, i would not say you're a dinosaur at all.

8:16 am

i don't know why you still have a blackberry. why do you still have a blackberry? >> host: e-mail. work e-mail. >> guest: these other two devices do a great job with work e-mail. >> host: i've gotten really good with my thumb on this thing. no? when did you give yours up? >> guest: oh, i never had a blackberry. i refused to use the one they issued at the journal. i used a palm trio. it wasn't about physical keyboards, it was about the ability to use apps and to do all kinds of different, cool things on the phone and to be more productive, actually, because there are loads of apps that are productive. and the blackberry never had very many apps and still doesn't. so, and it also, to me, had a very complex user interface. it really was designed as a corporate device. there's loads of, there's loads of consumers who use them, and i don't mean to insult anyone.

8:17 am

i could and you could probably show me as well, both of us could show videos and games and whatever you want to do on there, but it's a good e-mail device. but it's a good e-mail device mostly for corporate e-mail, or the i.t. department has decided you should use it. >> host: well, walt mossberg, we asked some reporters here in washington who cover tech policy if they had a question for you or anything, and gautham that fresh of cq had one to talk about the ipad. but he said how do you view microsoft's new tablet computer, and can they compete in hardware? >> guest: yeah. maybe we should explain to people that manager historic -- something historic happened last week which is that microsoft announced that it's building what i think is its first computer that it's ever built. happens to be a tablet, but it's a computer.

8:18 am

and it will run the new version of windows which is coming out in the fall which is kind of a tablet operating system and a particular windows that we know -- familiar windows that we know. it's a big gamble. we don't know whether that will appeal to consumers. but they decided to essentially adopt apple's model. microsoft and apple, of course, have been rivals for decades. and one of the big

8:19 am

>> guest: whereas a company like samsung, as good a company as it is, and it is, has to take android and kind of integrate it with their hardware, and the two things weren't made together. so to go to the question, first thing i would say is microsoft is, it's a historic thing. they've capitulate today the apple model. now, they're doing it to compete

8:20 am

with apple, but they tried it once before with the music player, but it was way too late, and it never took off. and now they're doing this. and the answer as to whether i think it can succeed is i haven't reviewed it yet. i haven't lived with it. i'm a reviewer, like a movie reviewer, except i review technology things. and i have seen it, i have fooled around with it for 10 or 15 minutes. i know the people that were behind it and understand the whole explanation of why they did it and how they did it. but my judgment really is always reserved for when i've had a chance to use it for at least a couple of weeks. so it looks good, and we'll just have to see. one issue is that they are -- it depends what you mean by "succeed." they're initially only going to sell it in limited outlets. microsoft has about 20 stores.

8:21 am

they have an online store. it looks like partly because of the politics of not wanting to, the delicacies of not wanting to compete with their own licensees like dell and lenovo and acer, they're going to not distribute it as widely as they might. >> host: elizabeth wasserman who is the editor of tech pro at politico wants to know will do not track features in web browsers solve the privacy problem, or are laws neededsome. >> guest: laws are needed. luckily, i am an opinion column it, not -- columnist, not a news reporter at "the wall street journal" in all things d, so i can have opinions, and it is my opinion that we need a serious, comprehensive, federal-level privacy law in the united states, digital privacy law.

8:22 am

i do not believe that the online advertising industry and other online businesses have been or will be successful at regulating themselves. and it's no different than other experiences we've had over the long history of the united states. i don't mean to sound like i want to go crazy and, quote, regulate the internet. on the other hand, i don't believe the internet should exist as a place outside the law. and, so, you know, here's an example of one thing that might happen. we know -- i know before i say this that the political climate in congress is never, ever this simple. but you could have a bill which simply said, peter, that your personal information which the law would define whatever it is, your name, your gender, your

8:23 am

age, your income, your address, your phone number, your e-mail, whatever, whatever 8, 10, 12 items they think of as your core personal informations, that that's your private property. and just say, and it should get treated like all other private property in the united states. we have a whole economy and a whole society built on private property. there are thousands of court cases and thousands of laws about the disposition and other thanship of private property -- ownership of private property. if you simply defined your information as private property, then maybe somebody would actually have to ask you permission. not opt out, but opt-in. can we use your private property to deliver ads? peter, can we use it? you could say, no, or maybe somebody would -- this is a radical idea, but i'm being facetious because we are a capitalist society, and i work for the wall street journal, why not pay you for it?

8:24 am

maybe your attitude is under no circumstances can you use it. maybe your attitude is i really don't care, go ahead and use it. but maybe your attitude is it's my private property, pay me something. give me a discount on your product, or give me five bucks, or give me five bucks a week, whatever it is, you know? we could actually have a whole business built up around the use of this. right now what happens is they simply take it, they make -- "they" being a whole collection of analytics companies and advertising companies and companies that depend on advertising like google and facebook -- they take this information, and you, the only thing you're given supposedly is targeted ads that you should enjoy more than nontargetted ads. i don't know about you, but i've been on the internet every day since it started, since it started as a -- the web started as a public thing, and i still

8:25 am

don't get ads that are targeted at my interests. so i don't think they've held up their end of the bargain and, yes, i think we need a privacy law. >> host: so what does rimm, google, apple know about me? >> guest: well, google -- i don't know about rimm. i don't know what their, you know, they're not that involved in social stuff. they -- c-span, if that's a c-span-issued phone, your i.t. department knows a certain amount about you because they and rimm together control the e-mail system on there. google knows a lot about you. if you use them. i don't know, maybe you don't use them. but if you use them for search and since you have an android phone, you use presumably some of their other services. they know a lot about you. i'm not saying they use it, but

8:26 am

we all do know there are some cases, a recent case still going on with the street mapping where they were collecting stuff out of people's wi-fi networks. they know a lot about you. apple also knows a hot about you. apple has been, has had a few slip-ups, but by and large apple's been much more conservative about your privacy. much to the consternation of, for instance, of magazine publishers and others. apple has not been willing to give them even your basic information unless you allow it. and that has annoyed a lot of the magazine publishers. so apple is more restricted, but they just bragged that they have 400 million customers whose credit cards they have. i don't mean that they stole the credit cards, i mean you when you signed up as a customer at itunes, entered a credit card just as you have presumably done at amazon or other places.

8:27 am

so they know a certain amount about you too. >> host: walt mossberg, in the past we've talked about companies such as aol, dell, and now we're talking about apple and microsoft. is one of the big five going to be a dinosaur in ten years? >> guest: oh, it's certainly possible. look, apple was 90 days from bankruptcy 15, 16 years ago. 90 days. after being the wunderkind ten years earlier. so, and now they're probably the single most influential tech company and one of the most influential companies in the world, and they're highly profitable, and their market capitalization's enormous. google didn't exist, you know, 30 years ago when the digital revolution got going.

8:28 am

so, yeah, any one of these guys can fail. one of the things that i love, actually, about covering the tech sector is people do fail, and it's not a stigma. if you fail, you can dust yourself off and come back and try to get funding, and often you can get funding if you come up with another good idea. and there's always a second chance. i mean, there's a lot of sectors of our society where failure really is a big stigma, and tech is not one of them. but the answer is any of these people can. it's very interesting. microsoft was being -- you haven't heard much about microsoft in the last fife or -- five or six years. they've been kind of behind the curve on phones and tablets and they still are. but this is going to be a year where there's a lot of microsoft excitement, and i think that's a great strength of the tech sector. companies are up, companies are down, new companies form, other companies go out of business. it's really the free market and

8:29 am

innovation and entrepreneurship at its best in our economy. >> host: walt moss berg, what's a piece of technology or an arc that's coming that you see that you're excited about? >> guest: well, you know, it's an overused term, but i think the cloud is an enormous thing. and what the cloud simply means is beginning to rely more on remote services, on servers somewhere out somewhere in the world that you get to through a relatively thin light device. i mean, this is -- there were -- may i touch this? >> host: yeah. >> guest: there were in the early '80s there were theories and papers written about having something thin and little like this that could nevertheless do all kinds of amazing things. part

164 Views

IN COLLECTIONS

CSPAN2 Television Archive

Television Archive  Television Archive News Search Service

Television Archive News Search Service

Uploaded by TV Archive on

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11